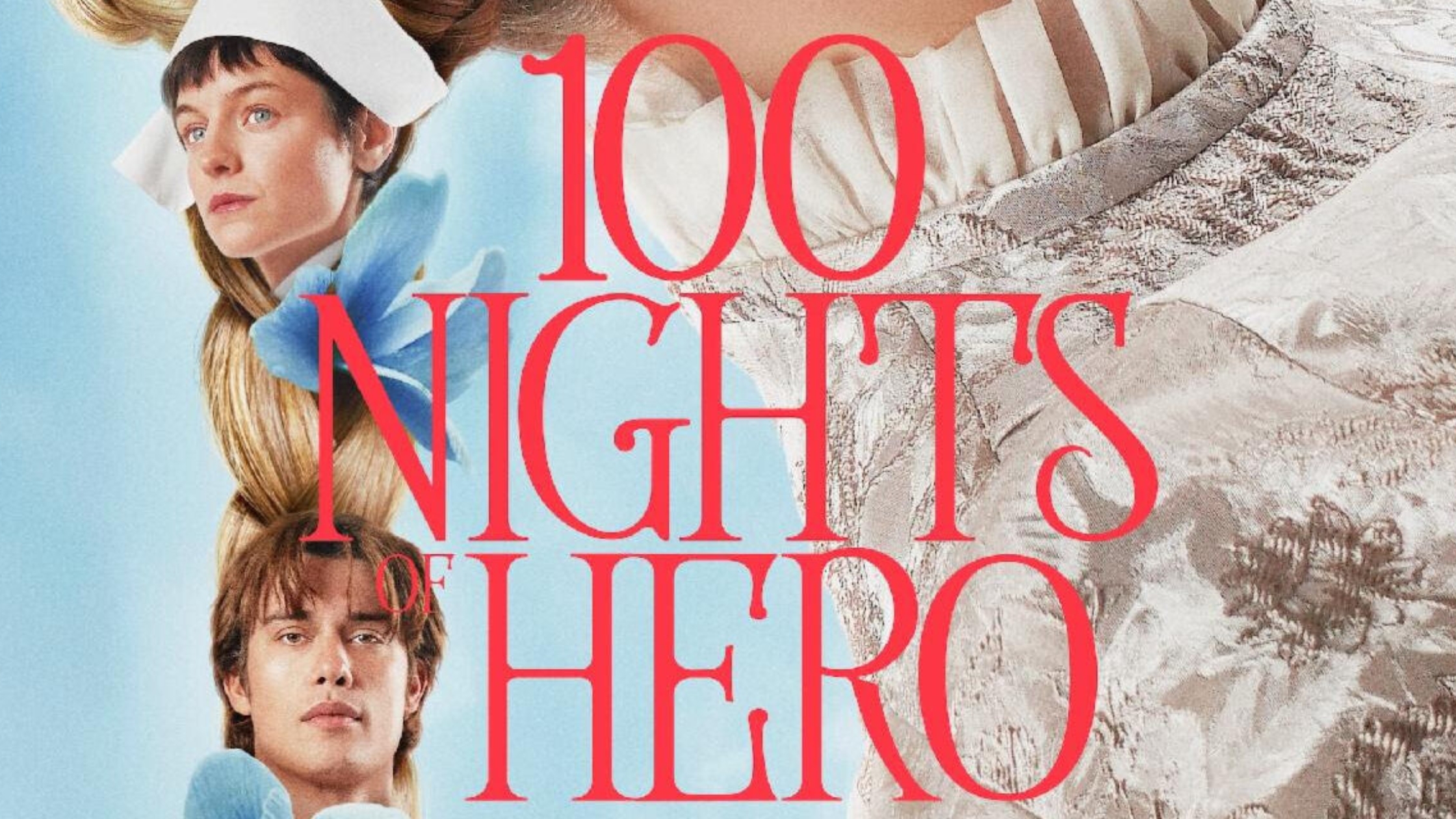

Movie blog — 100 Nights of Hero: a queer folktale, a maid with a story, and the art of outlasting a bet.

If you loved the intimacy of a chamber drama and the ornate pleasures of fairy-tale visuals, 100 Nights of Hero (2025) is the movie that quietly insists both can live in the same castle. Directed and written by Julia Jackman from Isabel Greenberg’s graphic novel The One Hundred Nights of Hero, the film translates a braided folktale about storytelling, fidelity and queer love into sumptuous period fantasy: colorful costumes, candlelit rooms, and a restless, clever maid who uses stories as strategy. It’s playful and earnest at once, a queer retelling of the “thousand nights” storytelling device that foregrounds women’s survival and subversive imagination.

Quick facts you can use as pull quotes.

Title: 100 Nights of Hero (2025) — directed & written by Julia Jackman.

Based on: The One Hundred Nights of Hero by Isabel Greenberg.

Key cast: Emma Corrin (Hero), Maika Monroe (Cherry), Nicholas Galitzine (Manfred), Amir El-Masry (Jerome), with Charli XCX, Richard E. Grant and Felicity Jones in supporting roles.

Runtime & production: ~90 minutes; a UK/US co-production with festival premieres (Venice, BFI LFF) and a scheduled U.S. release 5 December 2025.

How many cast members — and who actually carries this 100 Nights of Hero film?

The credits read like a compact treasure chest: the production surveys a dozen or so major players and a handful of memorable bit parts. If you count the leads (Hero, Cherry, Manfred, Jerome), the named important supporting players (Charli XCX, Felicity Jones, Richard E. Grant) and the smaller but narratively useful faces, you’ll be looking at roughly 12–20 credited cast members who matter to the plot — with many extra hands filling out the court, the servants, the guards and the storytelling circle.

But who carries the movie? That answer is simple: Hero, played by Emma Corrin. The narrative relies on Hero’s telling — her choice to counter male manipulation with tales of women outwitting men — and on the emotional gravity of her devotion to Cherry. Hero’s point of view and her storytelling craft are the film’s engine: she isn’t merely a witness, she’s an agent who transforms the fable itself into a weapon. Corrin’s performance is the film’s lodestar, with Maika Monroe’s Cherry as the emotional center she protects, and Nicholas Galitzine’s relentless Manfred as the external pressure.

Box office, release plan and the “numbers” truth.

This is a festival-first, art-minded release — not a franchise tentpole — so the usual box-office drama doesn’t dominate its life cycle. The 100 Nights of Hero film premiered at Venice (Settimana Internazionale della Critica) and closed the BFI London Film Festival, then attracted a U.S. theatrical release date (5 December 2025) with distribution by Independent Film Company in North America and Vue Lumière in the U.K. The production budget is modest (reported ~US$5.3 million), which means the film’s financial expectations are calibrated for festival buzz, limited theatrical play and downstream streaming or TV deals rather than blockbuster returns. Public box-office trackers show limited theatrical listings or “n/a” for early grosses — which is normal for small specialty films that lean on festival legs.

Put plainly: the measure of 100 Nights of Hero will be cultural reach and critical momentum more than raw box-office totals. Festival receptions (positive critics’ reviews, strong trade writeups) and platform deals will determine whether the film recoups modest costs and finds a long life on streaming or curated arthouse play.

The niche: where this 100 Nights of Hero movie fits and who should see it.

This is medieval-fantasy romance and queer fable, served as an intimate chamber piece. It sits in the niche of literary/fantastical arthouse: films that are shorter in running time, heavy on design and metaphor, and interested in gender, mythology and the politics of storytelling. If you like films such as The Love Witch, Pan’s Labyrinth (thematically), or modern queer reimaginings of folktales, 100 Nights of Hero is one of those rare festival finds that’s both playful and politically sharp. The film’s concerns — storytelling as survival, women’s agency in a patriarchal code, performance vs. authenticity — make it an especially resonant piece for viewers who value subtext and style.

Plot & deep narrative details (no spoilers held back).

At base, Jackman keeps the original folktale mechanics: a wealthy noble (Jerome) wagers with his friend (Manfred) — if Manfred can seduce Jerome’s wife, Cherry, within one hundred nights, the prize is huge; if he fails, the wager backfires. Jerome absents himself (as the husband commonly does in these tales), and Cherry is left in a remote castle under the watch of her maid, Hero. But the film complicates that simple triangular setup in three decisive ways:

- Hero is not passive. She is sharp-witted and literate in oral strategy. Where folktales often make the maid a mere helper, Jackman makes Hero the storyteller who rewrites male desire by reciting tales of women who survive, resist and reconfigure power. Hero’s nightly storytelling becomes an explicit tactic: each night she weaves a tale designed to weaken Manfred’s seduction, confuse his motives, or burnish Cherry’s inner life so she cannot be simply “won.”

- The romance is queer and nuanced. The heart of the movie is the relationship between Cherry and Hero. Their bond is tender and erotic in ways that resist the heteronormative stakes of the bet. Rather than treating Cherry as a prize, the film portrays a love that is mutual and quietly powerful: Hero’s vigilance is not servility; it’s devotion. That tonal shift — from a patriarchal wager to a queer love tale — gives the story modern ethical charge. Critics highlight how the adaptation foregrounds women’s solidarity as a political act.

- The antagonist is charisma turned weapon. Manfred (Nicholas Galitzine) is everything these tales ask for: handsome, irrepressible, charmingly predatory. Jackman keeps his seduction a repeated pressure — nights of performance, whispered promises, sensual theater — and uses those sequences to stage power as theatrical manipulation. The film’s tension comes from whether Hero’s stories can outpace Manfred’s performance. The narrative is therefore less a contest of bodies than a duel of narratives: seduction vs story.

Structurally the movie moves with a rhythmic clarity: nightly sequences (a new tale, a new test), daytime reflection (Hero and Cherry’s private exchanges), and the slow accumulation of emotional stakes. Jackman runs the film at a brisk ~90 minutes, which keeps its fairy-tale logic tight; the film never overstays its parable. Reviewers praise this economy even as they note occasional narrative interruptions from meta-structural flourishes.

What works (and why the film sticks with you).

- Visual design & costume — Susie Coulthard’s costumes and the production design create a tactile, theatrical world: think jeweled fabrics, claustrophobic castle interiors, and a color palette that feels like a storybook made real. Jackman leans into the theatricality, and the camera luxuriates in textures. Critics consistently praised the film’s visual pleasures.

- Emma Corrin as Hero — Corrin gives Hero a sharp intelligence and emotional generosity that anchors every scene. Their performance makes Hero’s storytelling feel alive, urgent and morally necessary.

- Queer feeling & narrative reframing — By making the central emotional bond queer, the film turns a classic seduction tale into a study of loyalty and queer desire. It’s a bold choice that refreshes the source material for contemporary audiences.

- Playful tonal balance — Jackman keeps the film light enough to be fun (there are frequent comic beats and whimsical set pieces) while maintaining the emotional seriousness of Cherry and Hero’s stakes. That blend of humor and ache is rare and effective.

What doesn’t always land.

Occasional narrative interruptions. Some critics find the meta-story devices — the film’s occasional nods to the frame tale or to other stories within the story — interruptive. The movie’s short runtime helps, but the structure sometimes keeps the viewer aware of adaptation more than immersion.

Economy vs depth. At ninety minutes the movie chooses concision over exhaustive character study. A few supporting characters (notably some members of the court) remain schematic; viewers craving deeper backstories may feel teased.

Why 100 Nights of Hero matters.

Adaptations of myth and folktale often retell old power structures without rethinking them. Jackman’s 100 Nights of Hero film does the opposite: it uses the familiar night-by-night storytelling framework to turn narrative itself into a feminist, queer tactic. That’s a useful cultural move in a time when stories are central to political identity: the film asks who gets to tell which story, and how those tales protect or endanger people. For festival audiences and queer viewers hungry for mythic queer romance, the film is a rare feast: short, beautiful, and—importantly—subversive.

Final verdict — who should see it and why.

100 Nights of Hero is for people who adore design-forward cinema that still carries an old moral (do not let someone else own your story). If you like playful reworkings of folktale logic, well-staged chamber storytelling, queer romance that refuses to be secondary and performances that do a lot with small gestures, book a ticket. If you prefer sprawling epics or character biographies that exhaust every motivation, this lean and allegorical fable may leave you wanting more detail — but it will likely leave you thinking about the power of narrative long after the curtains close.