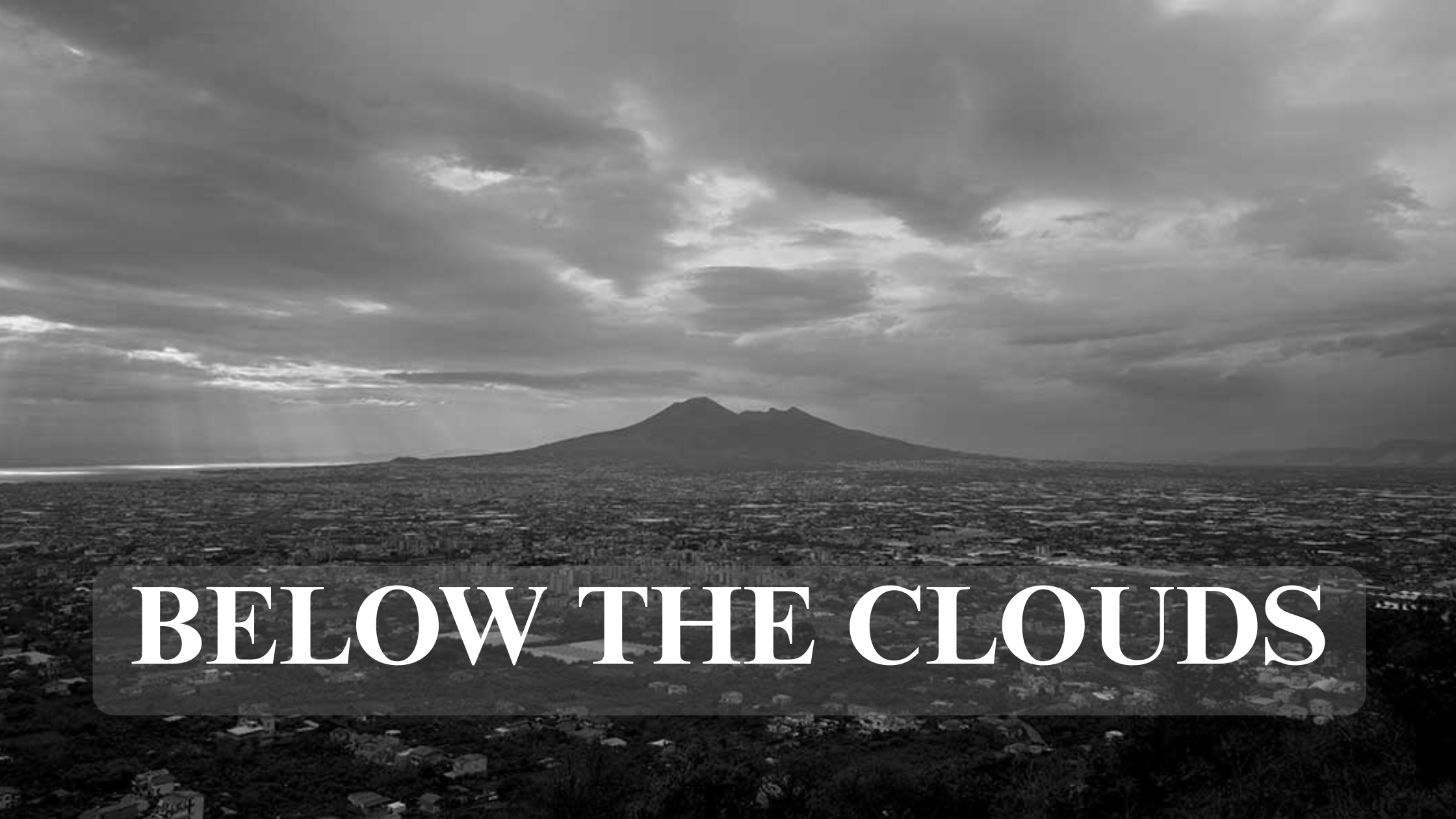

Movie blog — Below the Clouds (2025): Naples as Witness, Memory and Warning.

Gianfranco Rosi’s Below the Clouds is a film that refuses to be a city profile in the usual sense: it’s a long, black-and-white, unmannered meditation on Naples that treats people, ruins, rituals and the looming presence of Vesuvius as co-equal subjects. If you loved Rosi’s earlier documentary triptych — Sacro GRA (Rome outskirts) and Fire at Sea (Lampedusa) — this is the third act, an elegy and an archaeological survey at once. It’s less a linear story and more a mosaic of lives, images and small human economies that together add up to a powerful case for paying attention.

What kind of film is this — quick context.

Below the Clouds (Italian: Sotto le nuvole) is a 2025 documentary written, directed and photographed by Gianfranco Rosi. Shot over three years in and around Naples, it’s Rosi’s first feature in black and white in decades and—true to his practice—devoid of voiceover narration: the city speaks through its people, activities and recurring images. It premiered in competition at the 82nd Venice Film Festival (30 August 2025), where it won the Special Jury Prize, and later played festivals including TIFF and BFI London.

Cast? Not in the usual sense — the city is the “cast”.

This is important to get straight up front: Below the Clouds is not a drama with credited actors; it’s a documentary built from the real lives of Neapolitans — emergency-call operators, archaeologists, horse-trainers, migrant workers, students, tomb-raiders and shopkeepers. If you insist on a “cast count,” the film’s people number in the dozens across vignettes, but they are not listed like performers in a feature. The active subject in the movie is the city itself — Naples — and the people who inhabit its streets and institutions. Rosi’s camera treats them not as exemplars but as co-authors of a portrait.

That choice affects how you talk about “who carries the film.” There is no single protagonist. The real “means character” (the vantage point through which the film organizes meaning) is not an individual but a combination of two forces: Rosi’s observational gaze and the city of Naples. The director’s way of listening and selecting sequences shapes the film, but the recurring motifs — Vesuvius’ shadow, archaeological digs, emergency-call vignettes — are the narrative threads that carry the viewer through the whole piece.

Box office & release — small theatrical life, festival prestige.

This is a festival-first, art-house documentary that has a modest theatrical footprint by design. It opened theatrically in Italy on 18 September 2025 via 01 Distribution, and The Match Factory handles international sales with MUBI set to handle distribution across many territories (awards-qualifying runs in autumn, wider theatrical windows in early 2026). Early public box-office figures are small (IMDb lists a worldwide gross in the low five figures), which is typical: festival documentaries rarely chase blockbuster receipts; their currency is critical buzz, awards and long-tail streaming/licensing.

Put bluntly: if you measure success by multiplex grosses, Below the Clouds is not built for that metric. If you measure success by cultural traction — Venice Special Jury Prize, festival programming and likely art-house distribution via MUBI — it’s doing exactly what this kind of cinema is meant to do.

The film’s niche and tone — where it sits in the festival/arthouse ecosystem.

Rosi’s documentary sits in the rarefied niche of poetic, immersion documentary: observational, non-didactic, formally adventurous. Tonewise it is somber, often uncanny — the black-and-white photography gives Naples an atemporal look that can be both elegiac and apocalyptic. The film’s preoccupations are political and existential without resorting to headline journalism: climate threat, migration, labor precarity, decaying civic infrastructure and the afterlife of empires are handled through intimate scenes rather than didactic voiceover. If you follow auteur documentary — the kind that makes a city, a sea, or a border into a philosophical question — this is apex material.

What happens (briefly) — a mosaic, not a plot.

There isn’t a single plot to summarize. Instead, expect recurring motifs and sequence blocks:

- People at work: artisans, cleaners, horse-trainers and the Napoletani on the move.

- Emergency call centers and small acts of civic care that reveal both tenderness and systemic strain.

- Archaeological digs and tomb excavations — literal and cultural excavations that link contemporary poverty to layers of empire and disaster.

- Migrant scenes (Syrian sailors, workers) that show Naples’ role as a Mediterranean crossroads.

- Deserts of closed cinemas, burned-out buildings, and the pale, omnipresent outline of Vesuvius — a volcano as a civic emblem and metaphoric pressure cooker.

Rosi edits these sequences into a long poem: sometimes comic, sometimes bleak, often haunted. The film’s power is accumulative — images return, motifs echo, and the viewer begins to sense a civic psychology instead of a linear “what happens.”

Why the film matters — three big takeaways.

- It makes Naples thinkable as a whole rather than reduce it to tourist postcard — Rosi refuses easy sympathy or pity; he gives time for moods and contradictions. You see wealth and ruin, worship and crime, daily ritual and catastrophic memory folded together. That kind of civic portraiture matters in an age of headline simplifications.

- Form is argument — choosing black-and-white, long takes and no narrator is not mere style; it’s a political choice. The monochrome strips cinematic spectacle down to structure: light, shape and texture become the film’s rhetorical devices, which ask us to look differently at decay and survival.

- It’s Rosi’s formal trilogy closer — the film reads as the capstone of a three-film engagement with peripheral and island geographies of Italy (Sacro GRA, Fire at Sea, Below the Clouds). Each film listens to a place often ignored by easy national narratives; together they create a sustained reflection on borders and belonging.

What works — the film’s strengths.

- Lyrical cinematography & editing. Rosi’s own camera work and Fabrizio Federico’s editing produce images that lodge in the mind — the grain, the high-contrast frames, the recurring vistas of Vesuvius. These are the moments that keep returning in reviewers’ praise.

- The ethics of attention. Rosi sits with people rather than interrogate them. Even the morally ambiguous moments (tomb-raiding, institutional neglect) are presented in a way that prompts reflection rather than spectacle. Critics called it “haunting” and “luminous.”

- The film’s political breath. Beneath the lyricism is real social questioning: who cleans up after disaster, who gets buried (literally and figuratively), and who gets to make museums of other people’s lives. Rosi’s sequences about archaeologists and museum work are quietly scathing about entitlement and extraction.

What might divide viewers — the film’s price of ambition.

Pacing & patience. This is a two-hour, non-narrative documentary. If you want narrative propulsion or explanatory scaffolding, you will feel untethered. The movie asks for patient attention and rewards accumulative empathy rather than immediate answers.

Ambiguity as statement. Some viewers prefer documentaries that argue a thesis with clarity. Rosi’s mosaic approach is intentionally ambivalent; critics praise it but also note that meaning comes through montage rather than direct exposition. That can feel evasive to some.

Final verdict — who should see it and why.

Below the Clouds is essential viewing for cinephiles who care about documentary form, for anyone who loved Rosi’s earlier work, and for viewers willing to be patient and contemplative. It’s not a film you watch to “get” a single argument; you experience it to develop a civic imagination. Expect to leave with images that linger: a line of racehorses beneath Vesuvius, a close-up of dust being swept from an ancient relic, a call-center operator answering a trivial prank call before a truly urgent one arrives. Those moments accumulate into a picture of a city under pressure — wild, generous, haunted.

If you want to prioritize your viewing, catch it on the theatrical/art-house window (MUBI’s distribution is planned for many territories) or wait for the streaming release that will follow its awards run; either way, give yourself time and black-and-white patience.