Movie blog — Rose of Nevada (2025): a ghost trawler, time that sticks, and the salt-stung logic of grief.

Mark Jenkin’s Rose of Nevada is the kind of small-budget British oddity that arrives like a gift: hand-made, slightly abrasive, stubbornly unlike anything else on the screen. Built from 16mm texture, overdubbed sound and a formal approach that privileges repetition and echo over explanation, it’s a Cornish fable about a vanished trawler that returns to a derelict harbour — and about the people who get pulled into a past that won’t let them be. If you liked Jenkin’s Enys Men (2022) you’ll find the same dream-logic and tactile craft here; if you haven’t seen his work, think of a coastal Lynchian parable filmed with homemade technology and archaic cinematic rituals.

Quick facts you’ll want to know.

Director / Writer / Cinematographer / Editor / Composer: Mark Jenkin (he wears most of the hats).

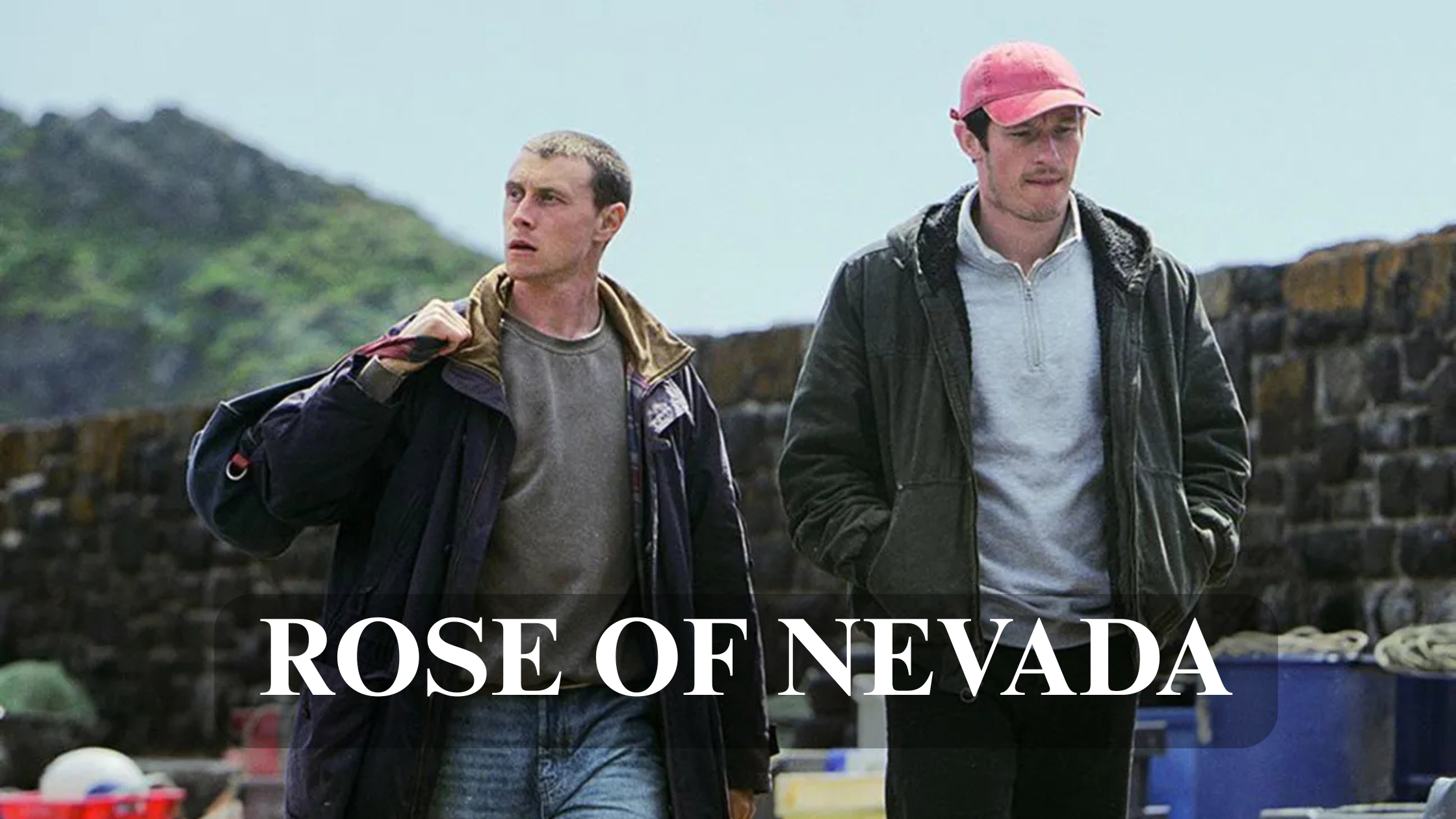

Principal cast: George MacKay (Nick), Callum Turner (Liam), Rosalind Eleazar, Edward Rowe, Francis Magee, Mary Woodvine and Adrian Rawlins among others.

Runtime: ~114 minutes. Country: United Kingdom.

Festival premiere: World premiere in the Orizzonti section at the 82nd Venice International Film Festival (30 Aug 2025); North American premiere in TIFF’s Special Presentations.

Early critical reception: Generally very positive on the festival circuit; critics praise the film’s formal daring and eerie atmosphere.

How many cast — and who literally carries the movie?

Jenkin uses a compact, village-scale ensemble rather than a wide Hollywood marquee: count on roughly 8–12 credited performers with narrative weight (Nick, Liam, the older locals, a couple who remember the original disappearance) and several non-professional faces that create texture. The marquee names are George MacKay and Callum Turner — both draw attention because they’re used to larger canvases, but here they’re handled almost as elements in a ritual.

Who “carries” the film? Formally, Rose of Nevada is ensemble-minded: the boat itself, the returning past, and the harbour community together do the heavy lifting. If forced to name a means character (the viewpoint that most often pulls us into the drama), you’d point to Nick (George MacKay). He’s the entry point: a man trying to provide for his family who signs up for a voyage on the mysteriously reappeared Rose of Nevada and then becomes consumed by dislocation when the boat takes its crew into 1993-time. But to describe the film as “Nick’s journey” would be reductive — Jenkin distributes intimacy among the village’s faces and makes place a character.

Box office & release context — small film, festival trajectory.

This is a festival and art-house play rather than a mass-market release. The film’s early life has been on the festival circuit (Venice → TIFF → NYFF), a standard model for British co-productions backed by Film4 and the BFI; Protagonist Pictures handles sales. Because of that pipeline, Rose of Nevada’s financial indicators will be modest theatrical runs, territory sales and long-term streaming/AVOD windows rather than blockbuster box office. Industry pages (e.g., The Numbers) catalogue the title but do not show big wide grosses — which is entirely expected for a film of this scale. In short: measure this film by critical momentum and cultural conversation, not opening-week receipts.

The niche — tone, audience and what the film wants to be.

Rose of Nevada lives where two audiences overlap: auteur-cinema devotees who love formally risky, handmade images, and viewers drawn to maritime folklore and ghost stories. Tonally it’s eerie and elegiac — a ghost-ship tale that prefers suggestion to explanation. Its formal choices (grainy 16mm, heavily processed audio, repetitive sequences) place it squarely in art-house, and thematically it speaks to people who like films that meditate on memory, community decline and the way coastal economies age and rot. If you want tidy answers, this film will be maddening; if you want to stay with mood, repetition and the slow accretion of dread, it rewards patient attention.

Plot (lean, spoiler-aware) — what actually happens.

The Rose of Nevada, a fishing trawler that vanished thirty years earlier with all hands, suddenly reappears in a run-down Cornish harbour. The village is exhausted — fish stocks gone, teenagers gone, the pubs half-closed — so when a working boat returns, people believe luck may finally turn. Nick (MacKay) and Liam (Turner) sign on for one voyage: they hope the trawler will bring money or at least work. Once at sea, strange things begin. The boat seems to carry the past like a weight; its acoustics and smells pull the men out of their present lives and, during one voyage, they find themselves transported back to 1993 — or at least mistaken for the missing crew who once sailed off and never came home. The Rose of Nevada film moves through repeated motifs — the same songs, the same radio broadcasts, the same gestures — until identity, memory and fate blur.

Jenkin isn’t interested in explaining how the time shift works. Instead the film treats time as a tide: it comes in, it takes things, it lays them down again changed. The more you watch, the more you feel the movie’s subject: how communities live with absence, how the past continues to demand restitution, and how the sea both preserves and erases memory.

Themes & what the film is thinking about.

- Return and repetition. The boat’s reappearance forces the town to confront the gap left by disappeared people — not just bodies but stories and livelihoods. Jenkin stages repetition (audio, motifs, rituals) so past and present resonate off one another.

- Working-class precarity and place. The village’s economic decline—empty harbours and lost industry—is as important to the narrative as supernatural disturbance. The film links grief to material decline.

- Identity and substitution. When Nick and Liam are mistaken for absent men, the film asks what identity means when your community needs you to be someone you are not — a haunting of social roles.

- Formal memory — cinema as artefact. Jenkin’s analogue methods (16mm; overdubbed sound) insist on cinema as crafted object, like a wooden boat — creaking, human, imperfect — and that aesthetic insistence underlines the film’s thematic insistence on the persistence of the past.

What works (and why critics like it).

Atmosphere & craft. Jenkin’s handmade textures—grain, scratch, manual sound design—create a cinematic climate that feels tactile and uncanny. Critics at Venice and TIFF emphasised the film’s eerie mood and how the methods amplify the story’s mythic quality.

Performances. MacKay and Turner resist star turns; they’re muted, tactile performers who fit into Jenkin’s ritual. The supporting cast (Edward Rowe, Rosalind Eleazar, Francis Magee) supply local detail and generational contrast.

Ambition in economy. For a film with modest resources, it feels bold — time-travel, supernatural suggestion and a community portrait, all executed with a clear formal point of view. Reviewers repeatedly call it “a bold, enigmatic work.”

What may not land for everyone.

- Patience required. Jenkin’s films reward immersion and annoyance in equal measure. Viewers wanting plot mechanics and clean timelines will be frustrated.

- Deliberate ambiguity. The film’s refusal to resolve its mystery is a feature, not a bug — but that feature will divide audiences who prefer narrative closure.

- Aesthetic specificity. The 16mm/overdubbed approach (voices out of sync, strange mixes) can be off-putting if you equate production polish with quality. Jenkin chooses texture over gloss.

Final verdict — who should see it and why it matters.

Rose of Nevada is one of 2025’s most interesting small-scale films: formally adventurous, thematically patient and emotionally quiet but persistent. It’s best for cinephiles who enjoy tactile film craft, viewers curious about contemporary British coastal stories, and anyone who appreciates mystery without exposition. For festival programmers and art-house operators it’s an easy recommendation; for mainstream audiences it will be an acquired taste — but a rewarding one once you surrender to its rhythms.

The Rose of Nevada film matters because it shows a confident auteur working in analogue materials, proving again that in an era of high-polish digital spectacle there’s still space for movies that feel hand-built and a little haunted. If you want to watch a movie that smells faintly of diesel and salt, that plays like a recorded folk nightmare, and that keeps bringing you back to the same image until it means more — Rose of Nevada is your next film.